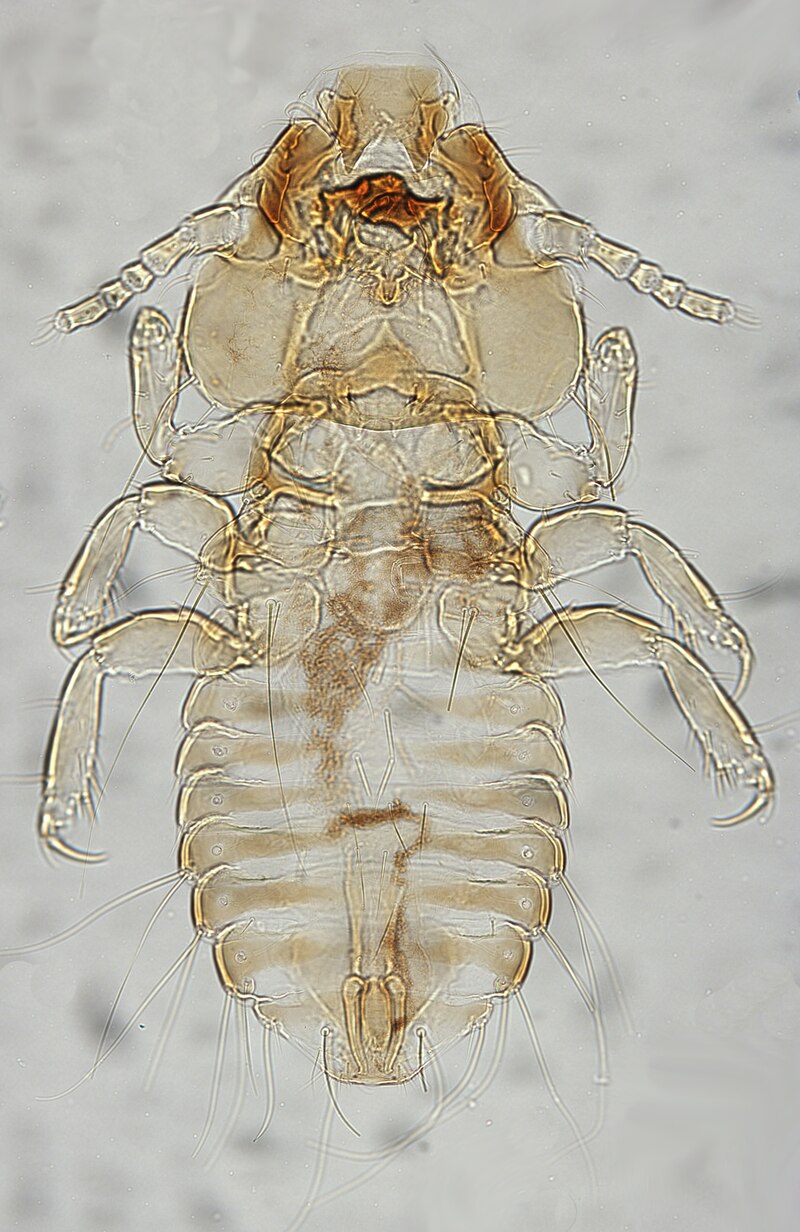

Mallophaga (chewling lice) are well known for their ability to chew through feathers and fur, but less known is their potential for phoresy (essentially using another organism as transit) on hippoboscids, a large group of parasitic flies. The reasons behind this are poorly understood but makes sense given the relative lack of ability lice have to move from one host to another without physical contact. This relationship is likely an underestimated part of the (at least ischnoceran) louse life cycle due to the way it helps the lice escape a dying host.

For an ectoparasite the death of a host can mean certain death and the means of escape are often less than effective, especially for something as tiny and specialized as a louse a hippoboscid fly offers a means to escape. Hippoboscidae supposedly attracts lice because they often have a higher temperature than the dead host. This heat is probably what led to the phoretic attachment in the first place, since it’s pretty easy to envision a scenario in which lice unknowingly attached to passing flies that made the mistake of landing on their dead/dying host.

The evolutionary benefits of escaping a dead host are very clear in the ischnocera. Risks are still high, as riding the hippoboscid can easily lead to death on an improper host and one would imagine that a louse that could not attach properly would quickly fall off, making the benefit of a free ride moot. Despite all these issues, ischnoceran lice in particular have some strong incentives to ride because they tend to cling to the feathers of their hosts even when the host dies.

Strangely enough, they are found on hippoboscids at much higher levels than the amblycera, who are more active after host death. This is likely due to the alignment in mandibles which are much more articulated for movement in ischnocerans as opposed to the stiffer amblyceran mandibles. This could facilitate attachment to the abdominal integument of the hippoboscid and be the trait that allows lice to ride hippoboscids with any decent chance of success. Amblycerans seem to have other ways to escape a dead host, as unfavorable as wandering into an inhospitable environment may seem. Ischnocera, however, have no other way out. Taking the risk inherent in phoresy is a better option than certain death, to be sure.

These are some of the few sources I was able to find:

Bequaert, J. “Phoresy of Mallophaga.” Entomologica Americana 12 (1953): 162-73.

Corbet, Gordon B. “The Phoresy of Mallophaga on a Population of Ornithomya Fringillina.” The Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine 92 (1956).

Keirans, James E. “A Review of the Phoretic Relationship Between Mallophaga and Hippoboscidae.” Journal of Medical Entomology 12.1 (1975): 71-76.

Macchioni, F., M. Magi, F. Mancianti, and S. Perrucci. “Phoretic Associations of Mites and Mallophaga With the Pigeon Fly Pseudolynchia Canariensis.” Parasite 12 (2005): 277-79.